Memory, Conflict and Class: Deindustrialisation in Belfast and County Durham Since 1970

Introduction

Political Background

The two case studies – both nationalised heavy industries – highlight the agency open to state actors when pursuing deindustrial agendas. Deindustrialisation, as Jim Phillips has written, ‘is a deliberate and willed human phenomenon’. Local political sensitivities influenced the time-scale, scope and intensity of shipyard deindustrialisation in Belfast. Loyalist/unionists equated British support for Harland & Wolff with British support for unionism, and portrayed reneging on shipyard aid as incipient economic evacuation from Northern Ireland. A group interview with retired welders reveals how some former shipyard workers feel exploited by unionist politicians. Rapid job losses against the backdrop of the Troubles, discussed by former storeroom clerk Maurice Davies, would have inflamed the security situation. Put simply, Harland & Wolff was protected because successive governments feared the grassroots backlash flowing from a closure decision. ‘Soft’ deindustrialisation was therefore applied – piecemeal dismantling, which was carefully stage-managed to shield the state from blame.

Policies applied to the National Coal Board/British Coal differed markedly, particularly after the 1984/5 miners’ strike. Steve Fergus discussed how Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government applied subtle (but significant) restrictions to British Coal’s commercial environment. Pit closures proceeded with minimal warning and consultation. The workforce was further demoralised by bullish management tactics, and lured with generous redundancy packages to accept closures. County Durham’s final coal mines were closed in 1993. In local authority areas such as Easington District, the economic lifeblood of many communities was eradicated at a stroke, with little planning – or hope – for adequate replacement. Geordie Maitland discussed the closure of Murton Colliery in 1991, arguing that pit closures were executed in an unnecessarily callous manner. Deindustrialisation is not inevitable and can be regulated if the political inclination exists.

Job Loss – Contested Perceptions

Industrial redundancy elicited myriad personal responses. For some, the loss of shipyard/pit employment marked a dramatic, and undesirable, life rupture. Fred Hoskins’ testimony is a stark example of this. Others recalled deindustrialisation as a kind of liberation, freeing them to pursue new careers in more rewarding and less dangerous jobs, or enjoy a long retirement. Former H&W manager Billy Harrison and Horden miner Gordon McDowell narrated their positive personal experiences of redundancy. Gordon’s testimony, nonetheless, was qualified with a hint of what Andrew Perchard has termed ‘survivor guilt’: acknowledgement that others (especially younger generations) faced bleaker circumstances. Deindustrialisation also challenged traditional gender relations and certainties, and was recalled differently by men and women. Maureen Foster, a former Women Against Pit Closures activist, discussed how coal industry redundancy could alter the domestic balance of power. Louise Jenkins made an insightful analysis of the age profile of redundant coal miners. She argued that where families were located on the “age spectrum” affected their job loss strategy. The quality and longevity of post-pit/shipyard employment was of critical importance in how people recalled the deindustrialisation process. Drew Shaw, a printer at H&W between 1959 and 1987, discussed his struggles, post-shipyard redundancy, to secure alternative employment and reluctant decision to withdraw (prematurely, in his view) from the labour market aged 57. Those that struggled economically post-redundancy were among the most critical of deindustrialisation.

Community Change

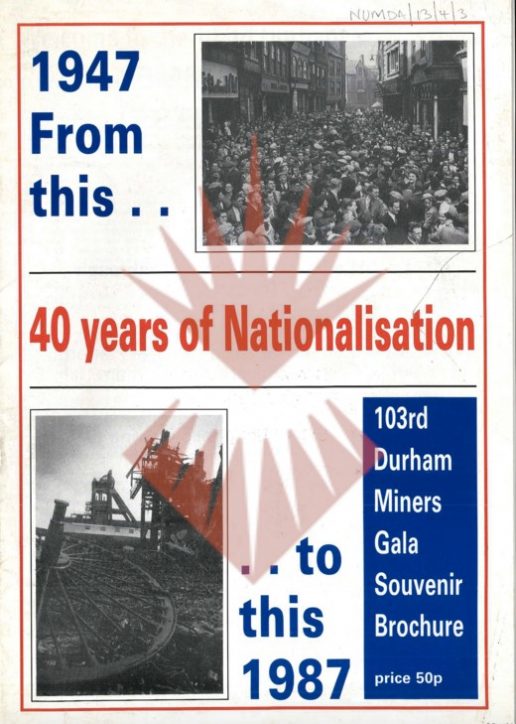

The demise of the industrial economy had significant social and cultural ripples, many of which can still be felt today. In mining communities in County Durham, the socio-economic scars of deindustrialisation are still visible. Unemployment and poverty rates rocketed, and remain above the national average. Industrial communities slowly disintegrated as many mining families moved out. In ex-pit villages private landlords, with negligible local accountability, purchased former NCB housing stock, supplying the local County Council with accommodation for “problem” tenants and people exported from other authority areas. Ex-miners Alan Johnson and Steve Fergus discussed the gradual and ongoing process of community change in their respective villages – Dawdon and Easington Colliery. Dave Douglass, a former National Union of Mineworkers official, talks to schools in the Doncaster area. Dave’s testimony gives a rather bleak impression of young people’s current economic opportunities, and sense of despair when confronted with stories of the (now absent) well-paid coal industry. He also commented that service sector employment tended to lack masculine-endowing prestige. The growing popularity of the annual Durham Miners’ Gala gives some grounds for optimism. At the “Big Meeting”, post-industrial communities are using the dead past of coal to reconstruct a sense of self and revive community cohesion.

In Belfast – particularly inner East Belfast, adjacent to the shipyard – the process of community change is murkier. The gradual nature of shipyard run-down protected these communities from catastrophic economic damage, argued ex shop steward Campbell Kell. The diverse nature of the city’s labour market also provided better job prospects for redundant shipyard workers, vis-à-vis redundant Durham miners. The removal of much of Belfast’s terraced housing system in the 1970s and 1980s also affected community integration as many families moved to new suburban estates. Gentrification has also played a part. Jackie Pollock reflected on the wider process of deindustrialisation in Belfast, and his assessment of the economic damage to East Belfast counter-balances some of the more optimistic social audits. Belfast’s Protestant working-class communities – formerly at the heart of Ulster’s industrial economy – are among the most deprived in Northern Ireland, and, for a variety of complex reasons, suffer from poor educational attainment levels and economic marginalisation.

Lived Legacies

The oral testimony used in this article paints a deeply fragmented picture of deindustrialisation. Despite the often negative socio-economic impact of closure on their lives and communities, few shipyard workers and coal miners wished for heavy industrial jobs to return. There was a degree of contentment that the industrial economy – in particular the damaging health effects associated with such work – had come to an end, albeit underpinned with criticism about how slowly economic regeneration has taken place. Reflecting on the heavy industrial economy, the shipyard welders group and ex-miner Stephen Jenkins foregrounded health hazards as a major factor behind their retrospective ambivalence about their former work. In Belfast and County Durham, the industrial economy has cast a long shadow. The cultural, economic and social aftershocks are still being felt, long after the initial moment of job loss and closure. Oral history is invaluable for unpicking the mixed meanings and complex social and cultural legacies of deindustrialisation.

This case study is written by Pete Hodson and uses oral history testimony collected for his PhD research.