The Holyland

The Holyland (also known as the Holylands) is an inner-city residential area located one mile south of Belfast City Centre.

Its name is a reference to the street names of the area, such as Carmel Street and Jerusalem Street, which were inspired by the developer’s trip to Egypt and Palestine in the 1890s. While the Holyland has no formal boundaries, it commonly refers to the streets enclosed to the west by Queen’s University, to the south by the River Lagan, to the east by Ormeau Road and to the north by University Street.

These interviews, with former and current Holyland residents, were recorded by undergraduate students on the module Recording History under the supervision of Professor Sean O’Connell. The testimony describes social and demographic changes from the 1940s to the present day. In the 1950s, the Holyland terraces housed a predominantly Protestant working-class community. Since the 1960s, the area has seen significant demographic shifts and currently houses a largely transient population of students and migrants. The following excerpts focus on four key themes: childhood, youth, demographic change and the arrival of large numbers of university students in the Holyland.

1940s–1950s: Childhood

The testimony reveals the range of leisure activities available to children in the 1940s and 1950s. While football and cricket were popular activities, the absence of cars meant that children also entertained themselves with improvised street games such as swinging on lampposts and ‘churchy one-over’.

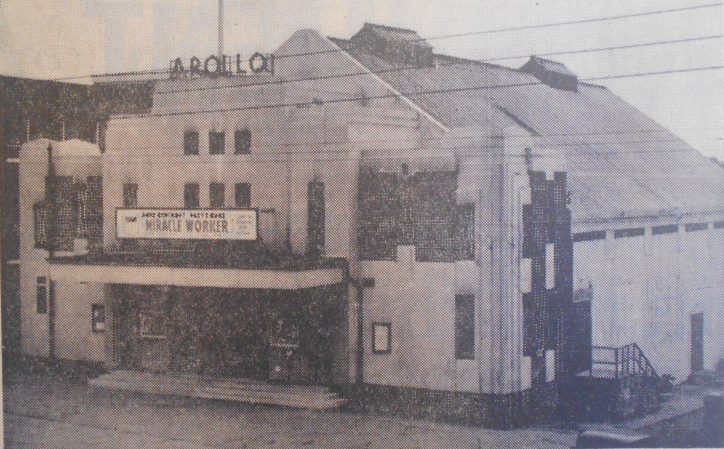

Children also played in the nearby Botanic gardens. Interviewees recall regular attendance at two local cinemas:the down-at-heel Apollo (now the Asian supermarket on Agincourt Avenue) and the more upmarket Curzon. Saturday morning matinees were particularly popular and the Roy Rogers Club—retitled the Curzon Children’s Cinema Club in 1959—operated from 1953 to 1970. There were also Saturday morning film screenings at the Belfast museum (now Ulster Museum).

Children also played in the nearby Botanic gardens. Interviewees recall regular attendance at two local cinemas:the down-at-heel Apollo (now the Asian supermarket on Agincourt Avenue) and the more upmarket Curzon. Saturday morning matinees were particularly popular and the Roy Rogers Club—retitled the Curzon Children’s Cinema Club in 1959—operated from 1953 to 1970. There were also Saturday morning film screenings at the Belfast museum (now Ulster Museum).

Several males recall the importance of the Boys’ Brigade in their social lives and many played football and joined the band in their local company. Alan’s excerpt shows that children often helped local businessmen on mornings and weekends to gain extra money and to supplement household income.

1960s: Youth

As children moved into adolescence, greater amounts of disposable income led them to spend more leisure time outside the Holyland. The interviews reveal the popularity of Belfast dance halls, such as Romanos, the Floral Hall and the Plaza. Increased car ownership and access to public transport meant that residents also frequented venues further afield, such as Caproni’s dance hall in Bangor.

As children moved into adolescence, greater amounts of disposable income led them to spend more leisure time outside the Holyland. The interviews reveal the popularity of Belfast dance halls, such as Romanos, the Floral Hall and the Plaza. Increased car ownership and access to public transport meant that residents also frequented venues further afield, such as Caproni’s dance hall in Bangor.

They were also more likely to attend larger and grander city centre cinemas, such as the Ritz, the Royal Hippodrome and the Gaumont. Cinemas and dance halls were both important courtship venues and provided opportunities for Holyland residents to meet partners from other parts of Belfast. In the 1960s, youth culture diversified and the range of social spaces available to young people expanded. Residents recall visits to Belfast’s pubs, nightclubs and jazz venues, and also recollect the emerging popularity of Northern Ireland’s showbands.

Liz discusses the significance of dancing and dance halls in post-war youth culture.

1950s–1980s Demographic Change

These excerpts reveal the demographic and social changes in the Holyland from the 1950s to the 1980s. Interviewees recollect the community spirit and family-centred nature of the Holyland in the 1950s. While the area was distinctly working class, residents recall the pride that people took in looking after their homes and the ‘respectable’ nature of the community. Interviewees also recall the importance of the male breadwinner and heads of households worked in places such as the shipyard, the docks and Gallaher’s Tobacco factory.

In the 1960s, Belfast witnessed centrifugal population shifts and many families moved away to new housing developments built by the Northern Ireland Housing Trust. From the late 1970s, it became a more socially and religiously mixed area and gained a reputation as a place of refuge from the Troubles, housing an eclectic mixture of punks, bohemians, students, lecturers and families. In the final excerpt, Petesy Burns explains the appeal of the Holyland for his emerging music collective in the mid-1980s.

The area was free of the overt sectarian problems that some other Belfast areas experienced and. Ann explains that the Holyland was mainly a Protestant district during the 1950s. Relations with Catholics were good but people were aware of the ‘subtle differences’ between people of different religions. Liz’s testimony reveals the extent to which strong community ties were often based on the family kinship networks: family members often lived on the same street. That began to change with the onset of the Troubles. Many Protestant families left the Holyland, moving to areas like Belvoir, and Catholic families from the Markets took their place. Meanwhile investors took the opportunity to buy some of the houses to rent to university students. The area also gained a bohemian image, most notably through its association with Punk: as Petesy explains.

1980s – Today: The Arrival of Students

In the 1990s, there was a dramatic rise in the number of students at Queen’s University and the University of Ulster. The demand for student accommodation increased and private landlords converted many of the Holyland’s traditional two-up two-down terraces into houses of multiple occupancy (HMO). Several interviewees lament these changes and discuss the role of the city planners, buy-to-let landlords and the students themselves in the changing nature of the Holyland. They describe the changing relationship between the traditional residents and the growing numbers of students and the problems caused by anti-social behaviour, particularly during St Patrick’s Day celebrations. In the past decade, the area has changed once more with many migrant families moving into the area: a development that has witnessed children playing in the streets of the Holyland once again.

Peter talks about his time as a student living in the Holyland, during the 1980s, and reflects on the changes he noted when he returned to Belfast in the 1990s. Emma recalls her time as a student in the late 1980s and 1990s, when the streets echoed to the sounds of the Stone Roses, and comments on the most recent demographic developments. The final interviewee, Mary, was interviewed on March 18th, the day after St Patrick’s Day, and this provoked some critical commentary on student behaviour in the contemporary Holyland and its impact on other residents.